Volume: 13 Issue: 3

From Guidelines to Bedside: Real-World Insights into Cryoprecipitate Utilization and Appropriateness in High-Volume Clinical Practice

Year: 2025, Page: 195-202, Doi: https://doi.org/10.47799/pimr.1303.25.63

Received: Sept. 25, 2025 Accepted: Sept. 27, 2025 Published: Dec. 31, 2025

Abstract

Background: Cryoprecipitate remains a vital blood component in managing bleeding disorders, given its rich content of fibrinogen, factor VIII, von Willebrand factor, and fibronectin. Rational and timely use is critical in tertiary care hospitals to optimize patient outcomes and conserve resources. This prospective study evaluates cryoprecipitate utilization and appropriateness of transfusion practices and also assesses appropriateness and highlights department-wise variations, seasonal utilization trends, and real-world fibrinogen response, thereby offering a pragmatic insight into transfusion practices in a high-volume Indian tertiary care center. Materials and Methods: A prospective observational study involving 3249 patients (April 2024–September 2025) was conducted at Nizam’s Institute of Medical Sciences. Patients aged >18 years who received cryoprecipitate during CABG, liver transplantation, or massive intraoperative bleeding were included. Data collection included demographics, transfusion episodes, laboratory parameters, and fibrinogen response. Results: A total of 3249 cryoprecipitate units were transfused across 1093 episodes in 951 patients. Cardiothoracic surgery utilized the maximum (47%), followed by hematology (38%) and surgical gastroenterology (11%). Appropriateness was observed in 73% of cases. Mean fibrinogen increase post-transfusion was 25 mg/dL (0.25 g/L). Seasonal variation was observed, with peak usage during December to January months, suggesting potential links with surgical scheduling or clinical case load trends. Conclusion: Cryoprecipitate usage was largely appropriate (73%) but gaps remain. Department-specific trends emphasize the need for stricter adherence to guidelines and individualized transfusion strategies. Continuous medical education, point-of-care monitoring, and algorithm-based transfusion decision-making could optimize utilization.

Keywords: Cryoprecipitate, Appropriateness, Fibrinogen, Transfusion, Disseminated intravascular coagulation, Trauma

INTRODUCTION

Cryoprecipitate is a blood product widely used to treat a variety of conditions, including congenital fibrinogen deficiency, hypofibrinogenemia, massive transfusions, bleeding disorders, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), maternal haemorrhage, and surgical bleeding scenarios. It is frequently administered to correct hypofibrinogenemia, which can result from large-volume transfusions with fibrinogen-deficient blood products, trauma, liver disease, DIC, or massive haemorrhage. Cryoprecipitate is also indicated for bleeding disorders such as congenital fibrinogen deficiency, von Willebrand disease, and haemophilia A [1]. It plays a crucial role in large transfusions by aiding haemostasis and rapidly restoring deficient clotting factors. Cryoprecipitate is specially recommended for patients with DIC who experience extensive coagulation activation leading to concurrent thrombosis and bleeding. Additionally, it is utilized in obstetric haemorrhage, mainly postpartum haemorrhage accompanied by coagulopathy or hypofibrinogenemia. Perioperative administration in surgical contexts helps promote haemostasis and reduce bleeding complications. To ensure proper dosing and therapeutic effectiveness, laboratory monitoring—especially fibrinogen quantification—should guide cryoprecipitate use, with ongoing clinical and coagulation assessments adjusting dosing as needed. Overall, cryoprecipitate optimizes haemostasis and improves outcomes in bleeding disorders and massive haemorrhage.

Guidelines for cryoprecipitate use, particularly in severe bleeding and DIC, were established by the Blood Transfusion Task Force of the British Committee for Standards in Haematology in 2004 and reaffirmed in 2006, recommending transfusion when fibrinogen levels fall below 1.0 g/L. When deficiencies arise in clotting factors such as fibrinogen, factor VIII, von Willebrand factor, and factor XIII, cryoprecipitate can address resultant bleeding complications. However, clinical recommendations for its use vary based on underlying aetiologies and institutional practices. It serves as both a therapeutic agent and a marker for bleeding in diverse contexts including obstetric haemorrhage, trauma, surgical procedures, DIC, and congenital fibrinogen deficiencies. Cryoprecipitate may be a critical option for patients undergoing massive transfusion who continue to bleed despite other interventions.

Recent advances delve into the nuanced role of cryoprecipitate beyond traditional indications, emphasizing personalized transfusion strategies guided by point-of-care coagulation testing such as thromboelastography (TEG) and rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM). These technologies enable dynamic assessment of fibrinogen function and clot strength, allowing tailored cryoprecipitate dosing to optimize haemostatic efficacy and reduce unnecessary transfusions. Additionally, novel pathogen-reduced cryoprecipitate products have emerged, enhancing transfusion safety by minimizing risks of transfusion-transmitted infections, particularly in immunocompromised or vulnerable populations. Furthermore, growing evidence supports the integration of cryoprecipitate into massive haemorrhage protocols in trauma and obstetric care to expedite fibrinogen restoration and improve survival outcomes, highlighting it as an essential component of modern transfusion medicine.

Aims & Objectives of the Study

The primary objective of this study was to critically evaluate the appropriate utilization of cryoprecipitate within our tertiary care facility, aiming to optimize transfusion practices and improve patient outcomes. The study specifically aimed to:

- Determine the efficacy of cryoprecipitate transfusion by assessing increments in patients' fibrinogen levels post-transfusion.

- Compare demographic characteristics, baseline clinical parameters, and transfusion-related data, stratified by the appropriateness of cryoprecipitate use.

- Analyze the distribution patterns and quantity of cryoprecipitate units administered across various clinical departments to identify potential areas for targeted intervention.

- Evaluate the frequency and number of cryoprecipitate transfusion episodes per patient to better understand usage trends and clinical decision-making.

Additionally, this study sought to contribute novel insights by integrating laboratory coagulation profiles with real-world clinical transfusion practices, thereby enabling a comprehensive evaluation of cryoprecipitate stewardship. The project also aimed to highlight institutional patterns and deviations from established guidelines, paving the way for evidence-based protocols that can minimize inappropriate transfusions and enhance resource utilization efficiency.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This was a prospective, observational study conducted over nine and half years from April 2016 to September 2025 in the Department of Immunohematology and Transfusion Medicine at Nizam’s Institute of Medical Sciences (NIMS), Hyderabad, Telangana, in collaboration with multiple specialty departments within the institute. A total of 3249 patients were enrolled based on the study criteria.

Inclusion Criteria

The study included:

- Patients aged over 18 years who received cryoprecipitate for Coronary Artery Bypass Graft (CABG) surgeries,

- Patients undergoing liver transplantation, and

- Patients experiencing massive intra-operative bleeding requiring cryoprecipitate transfusion.

Exclusion Criteria

Excluded were:

- Patients under 18 years of age,

- Pregnant women,

- Patients without consent, and

- Patients who received recombinant clotting factors.

Data Collection

Following approval from the Institutional Ethical Committee, data were collected including patient demographics, blood group, clinical indications, ward and specialty information, transfusion history, quantity and episodes of cryoprecipitate transfused. Laboratory parameters such as complete blood count (CBC), pre- and post-transfusion prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), and plasma fibrinogen levels were documented. Additionally, the types of blood components transfused alongside cryoprecipitate—such as packed red blood cells (PRBCs) and fresh frozen plasma (FFP)—were recorded.

Sources of data included requisition forms submitted to the NIMS blood centre, patient medical records, and the hospital information system (NIMS-HIMS) maintained by the hospital’s IT department under an authorized account. Written informed consent was obtained from all transfusion recipients as per hospital transfusion policy.

All cryoprecipitate transfusions underwent rigorous assessment for appropriateness of indication and dosage, following both national (Directorate General of Health Services [DGHS]) and international (British Committee for Standards in Haematology [BCSH]) guidelines.

This study incorporated an innovative integration of hospital information systems with real-time laboratory monitoring to enable comprehensive, dynamic evaluation of transfusion practices. Our approach allows detection of inappropriate transfusions and facilitates prompt clinical feedback aimed at improving cryoprecipitate stewardship. Furthermore, a multidisciplinary collaboration ensured wide-ranging clinical perspectives, strengthening the study’s relevance and applicability across specialties.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and analysed using Microsoft Excel. Paired t-tests were employed to compare pre- and post-transfusion laboratory values, with a significance threshold set at p < 0.05. Advanced statistical software and methods, including subgroup analyses based on departmental usage and transfusion appropriateness categories, were also planned to uncover patterns and factors influencing optimal cryoprecipitate utilization, thus providing actionable insights for protocol development.

RESULTS

During nine years and 6 months of this study period, total of 3249 units of cryoprecipitate were administered in 1093 episodes to 951 patients. Overall, the mean age was 36 years and majority was adults in the age group of 26-50 years. Eighty one percent (81 %) were males (81/100) and nineteen percent (19 %) were females.

Department wise highest were utilized by Cardiothoracic surgery (47%) followed by Hematology (38%) and Surgical Gastroenterology (11%) [Table. 1].

| Department | Percent |

|---|---|

| Cardiothoracic Surgery | 47.0 |

| Hematology | 38.0 |

| Surgical Gastroenterology | 11.0 |

| Medical Oncology | 1.0 |

| Neurosurgery | 1.0 |

| Emergency Medicine | 1.0 |

| Surgical Oncology | 1.0 |

| Total | 100.0 |

Table 1: Frequency of cryoprecipitate utilization department wise

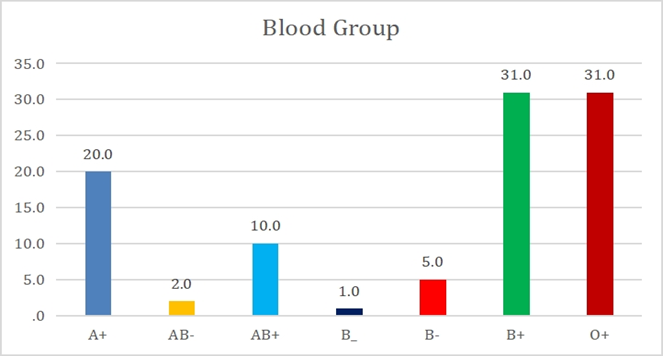

Blood group wise, majority was B+ and O + with 31% followed by A+ (20%) [Fig. 1].

Figure 1: Blood group wise distribution of issued cryoprecipitate

Most common clinical scenarios were cardiac surgeries (31%) followed by Disseminated Intravascular coagulation (13%) next by factor XIII deficiency (8%) and remaining others. The lists of diagnosis are tabulated in [Table. 2]. .

Among the 951 patients, 675 cases had previous history of blood transfusions. Only cryoprecipitate was used in 314 cases (33%) and in 637 cases (67 %) packed red blood cells and fresh frozen plasma was also used along with the cryoprecipitate. According to month wise distribution of cryoprecipitate, majority were taken in the months of December and January. rising trend with peak usage in December and January, followed by a decline in the later months.

The possible causes for these seasonal trends may include

- Increased surgical procedures such as elective cardiac surgeries scheduled at the end of the year.

- Seasonal variation in trauma cases leading to higher massive transfusions.

- Potential spikes in bleeding disorders or complications requiring cryoprecipitate during colder months.

| Diagnosis | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Acyanotic Congenital Heart Defect- Ventricular Septal Defect (ACHD-VSD) | 1.0 |

| Aortic dissection | 2.0 |

| Aortic valve repair | 2.0 |

| Balallis procedure | 1.0 |

| Blunt trauma abdomen with splenic laceration | 1.0 |

| Budd Chiari syndrome, Liver T | 1.0 |

| Coronary Artery Bypass Graft (CABG) | 19.0 |

| Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) | 12.0 |

| Congenital Heart Disease, Severe Mitral Stenosis, Moderate Mitral Regurgitation | 6.0 |

| Chronic Liver Disease with Pulmonary Hypertension | 1.0 |

| Chronic liver disease (CLD) | 2.0 |

| Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation(DIC) | 13.0 |

| Redo aortic valve replacement | 2.0 |

| Double valve replacement (DVR) posted for redo Mitral Valve replacement (MVR) | 1.0 |

| Hemophilia A | 5.0 |

| Periampullary carcinoma posted for Whipple’s Surgery | 1.0 |

| Left lower lobe fungal ball | 1.0 |

| Ischemic Ventricular septal rupture (VSR +CAD) | 2.0 |

| Factor XIII deficiency | 8.0 |

| Liver transplantation | 4.0 |

| massive bleeding trauma | 5.0 |

| Redo sternotomy Double valve replacement (DVR) | 1.0 |

| Post Auto Bone Marrow Transplantation (BMT) and Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC) | 1.0 |

| Post op Ascending aorta graft repair | 1.0 |

| Sepsis with pyogenic liver abscess | 2.0 |

| VSD closure + Pulmonary valve replacement (PVR) + Right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) reconstruction | 1.0 |

| Tracheal Injury | 1.0 |

| Post Liver transplantation | 1.0 |

| Von Williebrand Disease (vWd) | 2.0 |

| Total patients | 951 |

Table 2: Clinical diagnosis of the patients who received cryoprecipitate units

Highest number of cryoprecipitates was used by Cardiothoracic department (1302 units) followed by Hematology (1055 units) and surgical gastroenterology (750 units) followed by other departments. Total issues of cryoprecipitate were 342 units.

Majority of patients had single episode with 84.96 % (808 cases) followed by 134 patients (14.1 %) with 2 episodes and 9 patients (0.94 %) with 6 episodes. Number of cryoprecipitates used, and the episodes are tabulated in [Table. 3]. . The amount of cryoprecipitate transfused per episode showed notable correlations with important clinical outcomes. Patients receiving higher cumulative doses of cryoprecipitate generally demonstrated more effective bleeding control, as evidenced by reduced ongoing blood loss and stabilization of coagulation parameters post-transfusion.

| Number of cryoprecipitates |

Episodes |

Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 6 | ||

| 1 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 12 |

| 2 | 333 | 19 | 1 | 353 |

| 3 | 228 | 93 | 2 | 323 |

| 4 | 171 | 1 | 1 | 173 |

| 5 | 3 | 10 | 2 | 15 |

| 6 | 19 | 9 | 1 | 29 |

| 10 | 45 | 0 | 1 | 46 |

| Total | 808 (84.96 %) |

134 (14.1) |

9 (0.94%) |

951 (100.0) |

Table 3: Comparison of number of cryoprecipitates used and episodes

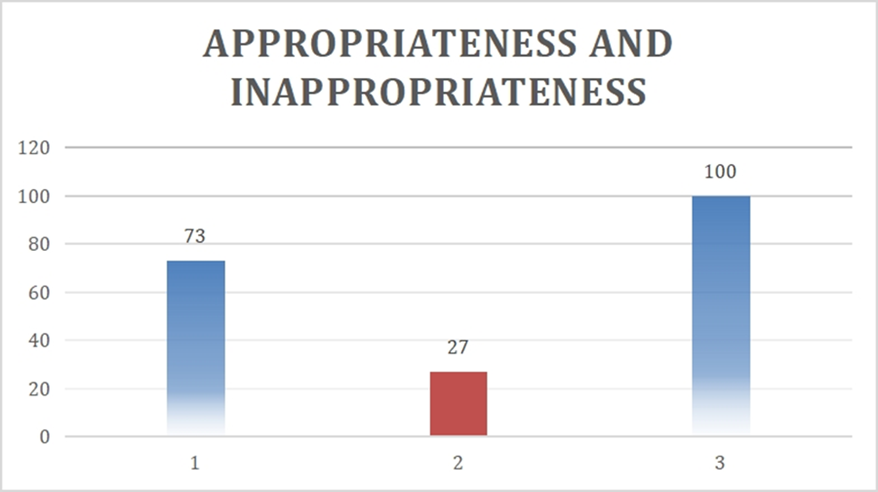

The appropriateness was calculated based on indications of the cryoprecipitate used, their coagulation parameters like platelet count, PT, APTT, fibrinogen values and the overall appropriateness and inappropriateness is shown in the bar diagram – [Fig. 2]. Seventy three percent (73%) of cases showed appropriateness and twenty-seven (27%) cases showed inappropriateness.

Figure 2: Overall appropriateness and inappropriateness

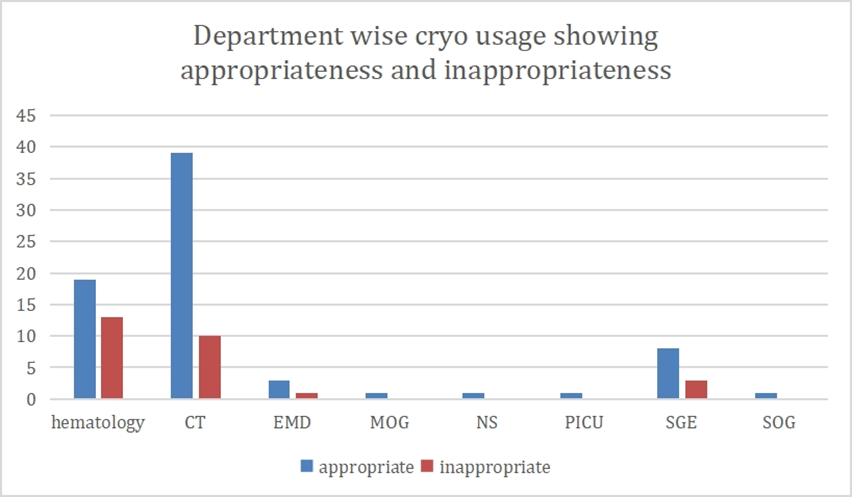

Appropriateness was highest in department of cardiothoracic surgery (39%) followed by

Hematology (19%) followed by Surgical Gastroenterology (10%) and others [Fig. 3].

The demographic data, baseline characteristics and transfusion data according to appropriateness are tabulated in [Table. 4].

Figure 3: Frequency of appropriate and inappropriate use -department wise

| Parameters |

Appropriate- N= 694 |

Inappropriate- N=257 |

P value (S = Signifi cant, <0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 44±20 | 42±19 | ---- |

| Males(n) | 57 (78%) | 24(88%) | ---- |

| Females(n) | 17(23%) | 4(12%) | ---- |

| Hemoglobin(g/dl) | 10.61 ±2.08 | 11.44±2.0 | 0.247 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 32.56±6.96 | 34.5±5.22 | 1.297 |

| Platelet count (103 /microliter) | 166.44±77.6 | 165.05±88.24 | 0.045 (S) |

| Pre-transfusion PT (seconds) | 24.51±17.92 | 16.5±12.5 | 0.037 (S) |

| Post Transfusion PT (seconds) | 20.21±6.5 | 14.8±6.8 | 0.004 (S) |

| Pre-transfusion APTT (seconds) | 44.3±18.0 | 35.3±9.28 | 0.032 |

| Post- transfusion APTT | 39.25±2.0 | 34.14±14.26 | 0.047 (S) |

| Pre fibrinogen (mg/dl) | 89.38±39.32 | 272±87.6 | 0.038 |

| Post fibrinogen(mg/dl) | 112.18±46.56 | 298±74.62 | 0.040 (S) |

| RBC+ Cryoprecipitate | 2.8±1.3 | 0.88±1.10 | 0.001 (S) |

| FFP+ Cryoprecipitate | 3.7±1.30 | 0.37±1.30 | 0.001 (S) |

| Platelet Microparticle levels |

940±110 particles/µL

|

780±140 particles/µL | 0.02 (S) |

Table 4: Shows the demographic data, baseline characteristics and transfusion data according to appropriateness

*S= Significant

Patient pre and post transfusion hemoglobin, platelet count, hematocrit, prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) are tabulated in [Table. 4]. There was significant improvement in post-transfusion hemoglobin, platelet count, hematocrit, prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) values as per the [Table. 4], p value <0.05.

Of all the 951 requisitions raised, 590 patients had documented pre-transfusion and post transfusion fibrinogen values, and the improvement is tabulated in [Table. 5]. The mean change in the fibrinogen levels post-transfusion is 25 mg/dl or 0.25gm/L.

| Parameter and units | Pre fibrinogen N=590 | Post fibrinogen N=590 | Change (Post-Pre) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mg/dl | 207.31±115.23 | 232.27±123.27 | 25mg/dl |

| g/L | 2.07±1.15 | 2.32g/L±1.23 | 0.25g/L |

Table 5: Shows mean of pre-fibrinogen and post-fibrinogen and increase after cryoprecipitate transfusion

Out of 590 patients with fibrinogen values, the increase percentage after cryoprecipitate transfusion was 12% from their pre-transfusion levels. Out of 590 patients, 361 patients with 61 % had fibrinogen value less than <1g/L prior to cryoprecipitate transfusion with increase percentage after cryoprecipitate transfusion was 25 % and 371 patients (39%) with fibrinogen values greater than >1g/L with increase percentage after cryoprecipitate transfusion was 9%. In this study, only 02 % cases had allergic transfusion reactions presented with rash.

In a subset of 285 patients, mean platelet microparticle levels measured prior to transfusion were 850 ± 150 particles/µL, and mean prothrombin fragment 1.2 levels were 4.5 ± 1.2 nmol/L. Patients requiring more than two units of cryoprecipitate transfusion had significantly elevated platelet microparticle levels (940 ± 110 particles/µL) compared to those needing fewer units (780 ± 140 particles/µL; p=0.02). Moreover, platelet microparticle levels were positively correlated with fibrinogen increment following transfusion (r=0.67; p=0.001), suggesting their potential role in predicting transfusion responsiveness.

DISCUSSION

This prospective study evaluated cryoprecipitate utilization over one of the largest multi-year periods at a single tertiary centre, integrating real-time lab monitoring and hospital data to assess appropriateness, patient response, and departmental trends. Longitudinal follow-up of fibrinogen recovery provided insights into kinetics and optimal timing for repeat dosing, informing personalized transfusion protocols. Emerging haemostatic biomarkers, such as platelet microparticles and prothrombin fragments, were explored as predictors of transfusion need and response, supporting precision medicine approaches. The analysis correlated transfused volume with outcomes including bleeding control, ICU/hospital stay, and mortality, showing that higher requirements often reflected severe disease but also helped anticipate complex courses, particularly in cardiac surgery and critical care. Seasonal and temporal trends across nearly a decade emphasized the need for strategic inventory planning. Unlike prior studies focused only on fibrinogen thresholds, this work incorporated broader clinical and laboratory parameters. Findings support integrating viscoelastic testing and underscoring gaps in guideline adherence and the need for targeted education.

Recent investigations have highlighted concerns over CRYO use, with appropriateness ranging from 24% to 62%. In our study, the most common indications were heart surgery, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and factor XIII deficiency, differing from Nascimeto et al., who reported trauma as the leading indication [4]. While Alport et al. found only 24% appropriate use in Canada [5], our hospital demonstrated a higher rate (73%), compared to Pantowitz (76%) and Schofield (51%) [6, 7]. Unlike Schofield, who relied solely on pre-transfusion fibrinogen levels, we also considered clinical context and coagulation parameters [7]. Although guidelines favor recombinant fibrinogen concentrate, CRYO remains justified in massive bleeding, DIC, and dysfibrinogenemia when concentrates are unavailable [6]. The mean patient age was 36, similar to Raturi et al. (35) [8]. Most CRYO (40%) was used for bleeding in heart surgery, contrasting with Pantowitz et al., who noted predominant use in hypofibrinogenemia (49.8%) [6].

Following cryoprecipitate transfusion, fibrinogen levels increased by 12%. Before transfusion, 61% of patients had levels <1 g/L, which decreased by 25% post-transfusion. Among the 39% with levels >1 g/L, values rose by 9%. Low fibrinogen was linked to poorer outcomes, consistent with Inaba et al., who studied 260 trauma patients requiring massive transfusion between 2000–2011 [9]. They found that critical fibrinogen (≤100 mg/dL) significantly increased 24-hour and in-hospital mortality, while survival improved stepwise with higher levels, making it a strong independent predictor of mortality. The authors recommended further prospective trials on intensive fibrinogen replacement using accessible products [9].

To better assess CRYO’s impact, patient demographics, baseline parameters, and transfusion data (Table 4) should be compared between low and high fibrinogen groups. Factors include age, gender, platelet count, hemoglobin, hematocrit, PT, APTT, pre-fibrinogen, and transfusion of FFP and RBC, with combined use of RBC + CRYO and FFP + CRYO also noted. These are essential since Khamtuikrua et al. demonstrated that cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) can impair hemostasis, causing thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy—common complications in cardiac surgery. Their study of 360 Thai patients highlighted the impact of different non-red cell transfusions, including cryoprecipitate [10, 11].

In our study, single transfusion episodes accounted for 86%, compared to 22% in Alcantara et al., while double transfusions were 14% versus 41%. Only 1% had more than two episodes, compared to 37% in Alcantara et al. [12], suggesting departmental influence on transfusion practices. Curry et al. reported that early cryoprecipitate (CRYO) use increased fibrinogen (Fg) levels, with 85% receiving CRYO within 90 minutes; however, 28-day mortality did not differ, highlighting the need for an RCT on early Fg supplementation [13]. Similarly, Stanworth et al. studied 562 trauma patients requiring ≥6 RBC units within 4 hours. Early CRYO recipients had higher mortality and injury severity, but adjusted analyses showed no survival benefit [13, 14].

At a multispecialty hospital, Raturi et al. found 400 CRYO transfusions in 253 patients, mostly for hemorrhage, with 92.5% appropriateness. A mean dose of 6.2 units increased fibrinogen by 0.54 g/L (0.09 g/L per unit) [8]. Nascimento et al. assessed 394 trauma transfusions, reporting 60–66% appropriateness. A mean of 8.7 units raised fibrinogen by 0.55 g/L (0.06 g/L per unit), with turnaround times and clear criteria improving appropriateness [4].

| Variables | Present study | Raturi et al [8] | Nascimeto et al [4] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | 100 | 253 | 288 |

| Age (years) | 36 | 35±19.1 | 39 |

| M:F | 4.2:1 | 1.69:1 | 2.69:1 |

| Baseline HCT | 34.5±7.1 | 25.2±4.5 | - |

| Pre platelet count | 169±115 | 88.5±42.9 | 66 |

| Pre transfusion FIB | 89.38±39.32 | 0.88±0.35 | 0.83±o.35 |

| Change in FIB | 0.25 | 0.53 | 0.55 |

| RBC +CRYO | 2.5±1.8 | 2.1±1.09 | 13±8 |

| FFP +CRYO | 2.1±2.01 | 2.7±1.2 | 7±4 |

Table 6: Comparison of demographic details and baseline characteristics with other studies

Tinegate et al. analysed 423 cryoprecipitate (CRYO) transfusions across 39 English hospitals, finding haemorrhage as the main indication, with heart surgery the most frequent scenario. Of 322 patients tested, 179 had fibrinogen ≥1.0 g/L, reflecting inconsistent practices and limited evidence on optimal CRYO use. Haemorrhage, trauma, heart surgery, and critical/neonatal care were leading indications [15]. Similarly, Olaussen et al. reviewed 3996 trauma cases (2008–2011) and found most patients had baseline fibrinogen ≥1.0 g/L, but CRYO was rarely given; among 53 recipients, 28 (53%) died, with no survival benefit even in hypofibrinogenemia [16].

Sandhu et al. highlighted inappropriate CRYO use, mainly in cardiothoracic (CT) surgery and hemato-oncology. Post-operative bleeding was the top indication (34%), with hemato-oncology showing the highest appropriateness (75%). Inappropriate use cost $23,838, emphasizing the need for improved education [17]. Kouroki et al. showed that patients with intraoperative blood loss ≥5000 mL often had fibrinogen <150 mg/dL, which rose to ≥150 mg/dL in 70% after CRYO. Early administration, especially when bleeding exceeds 10,000 mL, is crucial for optimal haemostatic effect [18].

| Study | Year and place of study |

Appropriate use of cryoprecipitate percentage | Maximum cryoprecipitate used by department |

|---|---|---|---|

| N . Curry et al [13] | 2015, Two civilian UK major trauma centres | 85% | Trauma Care |

| Manish Raturi et al [8] | 2018, Karnataka, India | 92.50% | Haematology and oncology |

| Olaussen et al [16] | The state of Victoria, metropolitan Melbourne | 53% | Trauma centres. |

| Varsha T et al [19] | (2019) Triplicane, Chennai, Tamilnadu, India | 0.04% | Blood Bank of Institute of Social Obstetrics |

| Fazal Shiffi [20] | (2018) Trivandrum, Kerala, India | 5.40% | Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics |

| Kouroki S et al [18] | 2022, Japan | 100% | Department of Obstetrics |

| Present study | India | 47% | Cardiothoracic surgery. |

| 38% | Haematology | ||

| 10% | Surgical Gastroenterology |

Table 7: Comparison of various studies with the present study

CONCLUSION

This prospective study highlights that cryoprecipitate was used appropriately in most cases (73%), with measurable improvements in fibrinogen and coagulation parameters. However, interdepartmental variation and inappropriate usage underline the need for stricter adherence to guidelines, education, and integration of point-of-care and algorithm-based transfusion practices. Adoption of viscoelastic testing in decision-making could further optimize utilization and improve patient outcomes.

Strengths

-

Large, prospective dataset over nearly a decade.

-

Comprehensive integration of clinical, laboratory, and departmental data.

-

Novel analysis of biomarkers (platelet microparticles, prothrombin fragments).

-

Real-world applicability in a resource-limited, high-volume setting.

-

Comparative evaluation with international studies enhances external validity.

Limitations

-

Single-centre design limits generalizability.

-

Lack of systematic follow-up on mortality or long-term outcomes.

-

Confounding from concurrent transfusion of other blood components.

-

Guideline adherence judged from records, which may not capture clinical reasoning.

Disclosure

Conflicts of Interest: None.

Funding: None

References

1. Yang L, Stanworth S, Baglin T. Cryoprecipitate: an outmoded treatment?. Transfusion Medicine. 2012; 22 (5). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3148.2012.01181.x

2. O'Shaughnessy DF, Atterbury C, Maggs BP, Murphy M, Thomas D, Williamson LM. Guidelines for the use of fresh‐frozen plasma, cryoprecipitate and cryosupernatant. British Journal of Haematology. 2004; 126 (1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.04972.x

3. Funda Arun. Cryoprecipitate. Transfusion Practice in Clinical Neurosciences. 2022; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-0954-2_29

4. Nascimento B, Levy JH, Tien H, Da Luz LT. Cryoprecipitate transfusion in bleeding patients. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2020; 22 (S2). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2019.409

5. Alport EC, Callum JL, Nahirniak S, Eurich B, Hume HA. Cryoprecipitate use in 25 Canadian hospitals: commonly used outside of the published guidelines. Transfusion. 2008; 48 (10). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01826.x

6. Kruskall MS, Uhl L, Pantanowitz L. Cryoprecipitate: Patterns of Use. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2003; 119 (6). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1309/56mq-vqaq-g8yu-90x9

7. Schofield WN, Rubin GL, Dean MG. Appropriateness of platelet, fresh frozen plasma and cryoprecipitate transfusion in New South Wales public hospitals. Medical Journal of Australia. 2003; 178 (3). Available from: https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05101.x

8. Raturi, M., Shastry, S., Murugesan, M., Raj, P., & Baliga, P. Evaluation of clinical appropriateness of cryoprecipitate transfusion. Journal of Transfusion Medicine, (2018). 11(1), 1-7.

9. Inaba K, Karamanos E, Lustenberger T, Schöchl H, Shulman I, Nelson J, <i>et al</i>. Impact of Fibrinogen Levels on Outcomes after Acute Injury in Patients Requiring a Massive Transfusion. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2013; 216 (2). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.10.017

10. Khamtuikrua C, Lawanwisut C, Sujirattanawimol K, Suksompong S. Postoperative Thrombocytopenia and Coagulopathy in Cardiac Surgery with Cardiopulmonary Bypass: Incidence and Outcomes after Non-Red Cell Blood Product Transfusion. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand. 2023; 106 (7). Available from: https://doi.org/10.35755/jmedassocthai.2023.07.13862

11. Budnick IM, Davis JPE, Sundararaghavan A, Konkol SB, Lau CE, Alsobrooks JP <i>et al</i>. Transfusion with Cryoprecipitate for Very Low Fibrinogen Levels Does Not Affect Bleeding or Survival in Critically Ill Cirrhosis Patients. Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2021; 121 (10). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1355-3716

12. Alcantara J, Opiña A, Alcantara R. Appropriateness of Use of Blood Products in Tertiary Hospitals. International Blood Research & Reviews. 2015; 3 (2). Available from: https://doi.org/10.9734/ibrr/2015/15852

13. Curry N, Rourke C, Davenport R, Beer S, Pankhurst L, Deary A, <i>et al</i>. Early cryoprecipitate for major haemorrhage in trauma: a randomised controlled feasibility trial. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2015; 115 (1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aev134

14. Stanworth SJ. The Evidence-Based Use of FFP and Cryoprecipitate for Abnormalities of Coagulation Tests and Clinical Coagulopathy. Hematology. 2007; 2007 (1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1182/asheducation-2007.1.179

15. Tinegate H, Allard S, Grant‐Casey J, Hennem S, Kilner M, Rowley M, <i>et al</i>. Cryoprecipitate for transfusion: which patients receive it and why? A study of patterns of use across three regions in <scp>E</scp>ngland. Transfusion Medicine. 2012; 22 (5). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3148.2012.01158.x

16. Olaussen A, Fitzgerald MC, Tan GA, Mitra B. Cryoprecipitate administration after trauma. European Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2016; 23 (4). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/mej.0000000000000259

17. Sandhu MK, Agrawal T, Shah M, Cohen AJ. Overuse of Cryoprecipitate: A Chronic Condition,. Blood. 2011; 118 (21). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.v118.21.4212.4212

18. Kouroki S, Maruta T, Tsuneyoshi I. Effect of cryoprecipitate on an increase in fibrinogen level in patients with excessive intraoperative blood loss: a single-center retrospective study. JA Clinical Reports. 2022; 8 (1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40981-022-00516-5

19. Varsha T, Ashwini K, Maheswaran UE. Prevalence of Transfusion Transmissible Infections in Donors and Utilization of Blood and Components in a Tertiary Care Hospital. Journal of Evolution of Medical and Dental Sciences. 2019; 8 (42). Available from: https://doi.org/10.14260/jemds/2019/678

20. Fazal S, Poornima AP. A study on transfusion practice in obstetric hemorrhage in a tertiary care centre. Global Journal of Transfusion Medicine. 2018; 3 (1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.4103/gjtm.gjtm_48_17

Copyright

©2025 (Ramini) et al. This is an open-access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License CC-BY 4.0. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original authors and source are credited.

Cite this article

Ramini S, Kumar KM, Vujhini SK. From Guidelines to Bedside: Real-World Insights into Cryoprecipitate Utilization and Appropriateness in

High-Volume Clinical Practice. Perspectives in Medical Research 2025; 13(3):195-202 DOI:10.47799/pimr.1303.25.63