Volume: 13 Issue: 3

Paediatric Cardiac Surgeries: A 15-Year Retrospective Study at Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital, Ghana

Year: 2025, Page: 170-177, Doi: https://doi.org/10.47799/pimr.1303.25.72

Received: Oct. 15, 2025 Accepted: Nov. 19, 2025 Published: Dec. 31, 2025

Abstract

Background: Congenital heart disease (CHD) is a major cause of infant mortality, with an incidence of 9.41 per 1,000 live births. In Africa, limited healthcare infrastructure makes CHD management particularly challenging. Over the past 15 years, Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital (KATH), Kumasi, has developed a paediatric open-heart surgery program. Aim: The primary aim was to characterise paediatric cardiac surgeries over a 15-year period and compare anaesthesia protocols before and after 2014. The secondary aim was to evaluate the impact of protocol changes introduced in 2014, including implementation of the WHO surgical safety checklist, adoption of early extubation, use of tranexamic acid, modified glycaemic control, and rationalised inotrope therapy. Materials and Methods: This single-centre, retrospective census-sampling review included 137 paediatric cardiac surgeries performed between October 2007 and September 2022. Patients were divided into Group A (before 2014) and Group B (after 2014). Institutional ethical approval was obtained, and data were analysed using SPSS version 23.0. Results: Compared with Group A, Group B demonstrated improved outcomes, including higher rates of ultra-fast track extubation (7.84% vs. 37.31%; P = 0.014), shorter ventilation times (82.34 ± 11.70 vs. 22.73 ± 6.49 hours; P = 0.028), reduced adrenaline (56.72 ± 10.46 vs. 17.36 ± 4.64 hours; z = 2.156) and dopamine use (13.26 ± 6.57 vs. 6.73 ± 2.38 hours; z = 1.977), lower postoperative chest drainage (133 ± 28.46 vs. 97 ± 15.83 ml; P = 0.036), fewer re-explorations for haemorrhage (11.77% vs. 1.21%; P = 0.018), and shorter mean hospital stay (6.87 ± 3.51 vs. 4.18 ± 3.52 days; P = 0.047). More patients required no inotropes in Group B (22.89% vs. 9.81%; P = 0.026). Conclusions: Systematic protocol changes after 2014 significantly improved perioperative outcomes despite resource limitations. These findings demonstrate the value of adapting the best global practices to local contexts in low- and middle-income countries.

Keywords: Anaesthesia, Congenital heart disease, Ghana, Open heart surgery, Paediatric cardiac surgery

INTRODUCTION

Congenital heart disease (CHD) refers to structural and functional abnormalities of the heart that are present at birth. If not managed through timely and appropriate interventions, CHD can significantly impact an individual’s quality of life and may lead to premature death. It is the most common birth defect, affecting approximately 1–2% of all live births globally, with an estimated incidence of 9.41 per 1,000 live births [1]. The prevalence of CHD for sub-Saharan African children varies from 2.2 to 14.4 per 1,000 live births [2]. According to reports from the World Health Organisation (WHO), approximately 240,000 newborns die each year from CHD within the first 28 days of life. Additionally, approximately 170,000 children die before reaching their sixth birthday due to CHD [3]. However, the estimated under-5 mortality for sub-Saharan Africa is 76/1,000 live births. Six countries from this region have mortality rates >100/1,000 live births, among the highest in the world. This translates to 16,000 per day dying before their fifth birthday [4]. The precise prevalence and distribution of CHD in Ghana remain inadequately characterised due to limited population-based data. Nevertheless, a retrospective five-year review of echocardiographic records at the National Cardiothoracic Centre, conducted between January 2006 and December 2010, reported that 60.3% of the 4,823 echocardiograms performed were attributable to newly diagnosed CHD [5]. In Ghana a population-based prevalence of 5.12 per 1,000 children, and a hospital-based prevalence of 12.63 per 1,000 [6].

Infrastructure for cardiac surgery in Africa is sparse, with only one cardiac centre available for every 50 million people, compared to one per 1.15 million in Europe and the United States. Fewer than 5% of individuals have access to cardiac care. In the absence of timely and accessible treatment, one in three children born with CHD die within the first month of life [7]. Globally, an estimated 1.3 million children are born with CHD each year; however, fewer than 100,000 receive the necessary cardiac care, leaving more than one million without treatment annually [3]. Over time, this contributes to a significant backlog of untreated cases.

Ghana is one of the four countries in West Africa regularly performing open-heart surgeries, alongside Nigeria, Senegal and Ivory Coast. While Ghana’s National Cardiothoracic Centre in Accra is the country’s primary accredited centre, Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital (KATH) in Kumasi has developed and sustained a paediatric cardiac surgery program since 2007. KATH, a major tertiary referral centre in Ghana, serves about 9.7 million people, receives referrals from 13 regions of Ghana and neighbouring countries, has more than 1,000 beds, and manages 40,000 inpatients and 380,000 outpatients yearly [8]. There remains a scarcity of long-term data from low- and middle-income developing countries (LMICs), particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. This lack of data limits our understanding of surgical outcomes, resource utilisation, and the unique challenges faced in these settings.

In West Africa, where access to specialised cardiac care remains limited and health systems face considerable constraints, there is an urgent need to assess past performance to guide future practices. Retrospective studies are especially valuable in such contexts, as they offer insights into trends, outcomes, and institutional progress over time.

The primary aim of this study is to evaluate trends, outcomes, and evolving anaesthetic practices in paediatric cardiac surgery within a resource-limited West African tertiary hospital. Secondary aims include assessing perioperative complications, mortality, quality improvement measures, and protocol changes, while identifying gaps to guide future care in LMICs.

The findings from this study will contribute to the global body of evidence on paediatric cardiac care in LMIDCs. Additionally, they will support informed policymaking, targeted training, and effective resource allocation at both institutional and national levels.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a single-centre, retrospective, Census Sampling chart review of 137 paediatric cardiac surgeries performed between October 2007 and September 2022 at Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital (KATH). Institutional approval was obtained from the Research and Development Unit at KATH No. RD/CR16/295. All necessary precautions were taken to protect patient confidentiality. The Ethics Committee waived the requirement for individual written consent. Permission to access patient records for anaesthetic and surgical data was obtained from the Directorates of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, and Surgery. Each open-heart surgery (OHS) case was assigned a unique computer-generated code for research purposes.

KATH serves a population of approximately 9.7 million people across three regions of Ghana. It is a major referral hospital, receiving patients from 13 of the country’s 16 regions, as well as from neighbouring countries such as Ivory Coast and Burkina Faso. The hospital has a capacity of more than 1,000 beds and handles over 40,000 inpatients and 380,000 outpatients annually [8, 9].

The study included all paediatric cardiac surgeries performed during the study period. Patient records with insufficient data and those involving individuals over 18 years of age were excluded. United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), the 1992 Fourth Republican Constitution of Ghana, and the Children's Act 1998-Act 560). legally and ethically, anyone under 18 years is considered a child in Ghana, consistent with CRC, the 1992 Constitution, and Act 560 [10].

This study aimed to characterise paediatric cardiac surgeries over the past 15 years, with a particular focus on trends before and after 2014. We compared anaesthesia protocols in a low-resource setting, highlighting key changes introduced after 2014, including implementation of the modified WHO operating room safety checklist, adoption of early extubation to reduce ventilator-associated complications, the use of tranexamic acid (TXA) to limit postoperative haemorrhage, a shift away from strict glycaemic control to minimise hypoglycaemia, and rationalised inotrope use tailored to patient needs to reduce arrhythmia risk.

Routine perioperative data were collected and analysed using 32 clinical variables. The Shapiro–Wilk test was employed to assess the normality of data distribution. Continuous variables were expressed as means with standard deviation (SD) and compared using Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate. Categorical variables were analysed using Fisher’s exact test or Chi-square test. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences SPSS 23.0, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA for Windows.

RESULTS

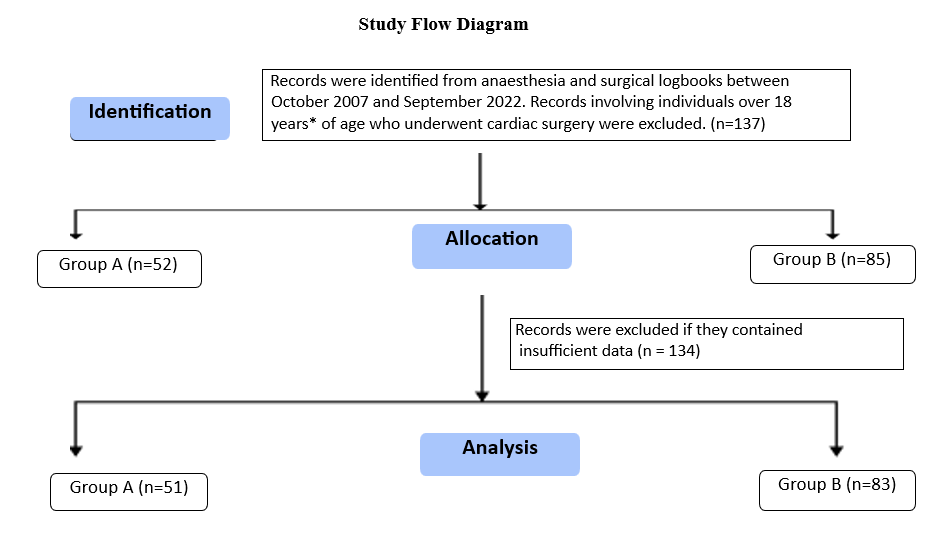

In total, 137 patient charts were reviewed, and 134 patients with complete data were included in the final analysis, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Study Flow Diagram: Paediatric Cardiac Surgery Patients

*(United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), the 1992 Fourth Republican Constitution of Ghana, and the Children's Act 1998-Act 560).

As shown in Table 1, the demographic profiles of the cohort were comparable (p>0.05). The patients’ median age (years), weight (kg) and Body Mass Index (BMI) kg/m2 were 5.57± 1.26, 5.73 ± 1.73 and (P = 0.352),16.72 ± 2.69 and 17.63 ± 2.74 (P = 0.567) and 15.80±0.72, 15.30±0.56 and (p=0.742) in Groups A and B, respectively. The male-to-female ratios were 1:1.74 and 1:081 in Groups A and B, respectively (P = 0.138), as shown in Table 1.

| Parameter | Study (n=137) | Group A (n=52) | Group B (n=85) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD |

Mean ± SD |

|||

| Average patient age (years) | 5.68±1.40 | 5.63±1.06 | 5.73±1.73 |

0.352 |

| Average patient weight (kg) | 16.03±1.72 | 16.42±0.69 | 15.63±2.74 |

0.567 |

| BMI kg/m2 | 15.56±0.64 | 15.80±0.72 | 15.30±0.56 |

0.742 |

| Sex, ratio (%) | ||||

| Male | 1 (48.18 %) | 1 (36.54%) | 1(55.29%) |

0.138 |

| Female | 1.08 (51.82 %) | 1.74(63.46%) | 0. 81(44.71%) | |

Table 1: Demographic profile of cardiac surgeries

Data presented as means ± SD, a P<0.05, was considered statistically significant. BMI: Body Mass Index, SD-Standard deviation.

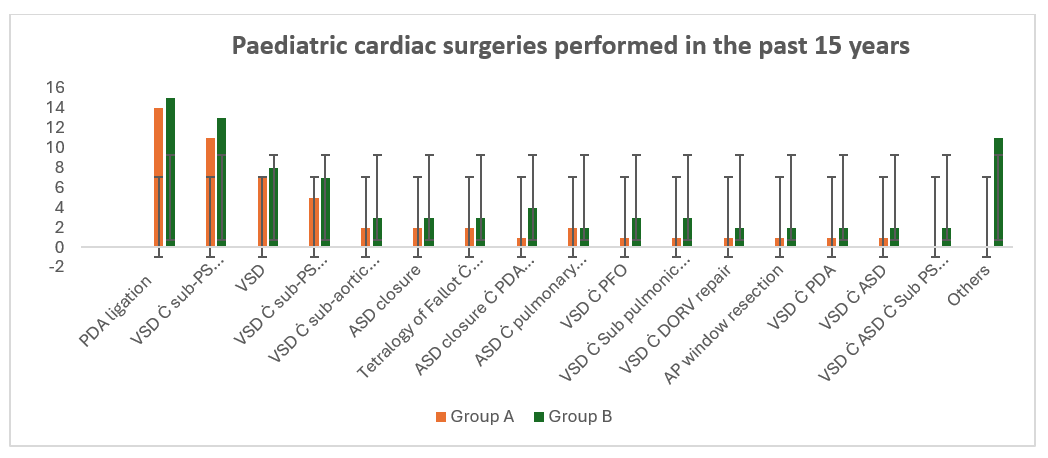

Table 2 and Figure 2, showing the types of surgeries performed at KATH between October 2007 and September 2022 included closure of atrial septal defects (ASD), ligation of patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), repair of double outlet right ventricle (DORV), and closure of ventricular septal defects (VSD).

| Type of surgeries performed |

Study (n=137) n, (%) |

Group A (n=52) | Group B (n=85) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDA ligation | 29 (21.17%) | 14 | 15 |

| VSD C sub-PS resection C infundibular patch (which was nontrans annular) | 24 (17.52%) | 11 | 13 |

| VSD | 15(10.95%) | 7 | 8 |

| VSD Ċ sub-PS resection Ċ transannular patch | 12(8.76%) | 5 | 7 |

| VSD Ċ sub‑aortic membrane resection | 5(3.65%) | 2 | 3 |

| ASD closure | 5(3.65%) | 2 | 3 |

| Tetralogy of Fallot Ċ BT Shunt | 5(3.65%) | 2 | 3 |

| ASD closure Ċ PDA ligation | 5(3.65%) | 1 | 4 |

| ASD Ċ pulmonary valvulotomy | 4(2.92%) | 2 | 2 |

| VSD Ċ PFO | 4(2.92%) | 1 | 3 |

| VSD Ċ Sub pulmonic stenosis Ċ pulmonary valve replacement | 4(2.92%) | 1 | 3 |

| VSD Ċ DORV repair | 3(2.19%) | 1 | 2 |

| AP window resection | 3(2.19%) | 1 | 2 |

| VSD Ċ PDA | 3(2.19%) | 1 | 2 |

| VSD Ċ ASD | 3(2.19%) | 1 | 2 |

| VSD Ċ ASD Ċ Sub PS Ċ infundibular patch (nontrans annular) | 2(1.46%) | - | 2 |

| VSD Ċ ASD Ċ mitral valve annuloplasty | 1(0.73%) | - | 1 |

| VSD Ċ PFO Ċ PDA | 1(0.73%) | - | 1 |

| VSD Ċ sub‑aortic membrane resection Ċ mitral valvuloplasty | 1(0.73%) | - | 1 |

| VSD Ċ pulmonary valve commissurotomy | 1(0.73%) | - | 1 |

| VSD Ċ aortic valve reconstruction | 1(0.73%) | - | 1 |

| Subaortic membrane takedown | 1(0.73%) | - | 1 |

| DORV repair | 1(0.73%) | - | 1 |

| Posterior mitral valve annuloplasty (Cosgrove band Ċ closure of mitral valve cleft) | 1(0.73%) | - | 1 |

| Sub pulmonic stenosis resection + transannular patch | 1(0.73%) | - | 1 |

| Partial anomalous pulmonary venous return repair Ċ ASD repair | 1(0.73%) | - | 1 |

| Pulmonary valve commissurotomy Ċ PFO closure | 1(0.73%) | - | 1 |

Table 2: Types of surgeries performed over the past 15 years

Ċ: With, ASD: Atrial septal defect, DORV: Double outlet right ventricle, PDA: Patent ductus arteriosus, PFO: Patent foramen ovale, PS: Pulmonary stenosis, VSD: Ventricular septal defect, BT: Blalock-Taussig

Figure 2: Ċ: With, ASD: Atrial septal defect, DORV: Double outlet right ventricle, PDA: Patent ductus arteriosus, PFO: Patent foramen ovale, PS: Pulmonary stenosis, VSD: Ventricular septal defect, BT: Blalock-Taussig

To compare the complexity of cardiothoracic surgeries between the two groups, the Ross preoperative functional classification/NYHA class and Aristotle’s Comprehensive Complexity (ACC) scores were used, as detailed in Table 3. The mean ACC score over the study period was 7.25 ± 0.35, with Group A scoring 6.9 ± 0.33 and Group B scoring 7.6 ± 0.37. All surgeries were classified as ACC Level 2 (range: 6.0–7.9). This result indicates that the difference in ACC scores between the two groups is not statistically significant at the conventional alpha level of 0.05 (since |Z| < ±1.96).

Although small differences were observed in the distribution of NYHA/Ross functional classes, these were not statistically significant. This suggests that both groups had comparable preoperative functional status, and that baseline severity (as classified by NYHA/Ross class) was similar across the groups.

| Classifications | Group A | Group B | Z- value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n=52) | (n=85) | ||

| ACC level: (mean ± SD) | 6.9±0.33 | 7.6±0.37 | -1.41 |

| NYHA/ross preoperative functional class (n) %: | |||

| I | (24) 46.15% | (41) 48.24% | -0.24 |

| II | (25) 48.08% | (36) 42.35% | 0.65 |

| III | (3) 5.77% | (8) 9.41% | -0.76 |

Table 3: Complexity level of surgeries

*P<0.05 significant, CL‑95%, Z critical value ±1.96. ACC: Aristotle SD-Standard deviation.

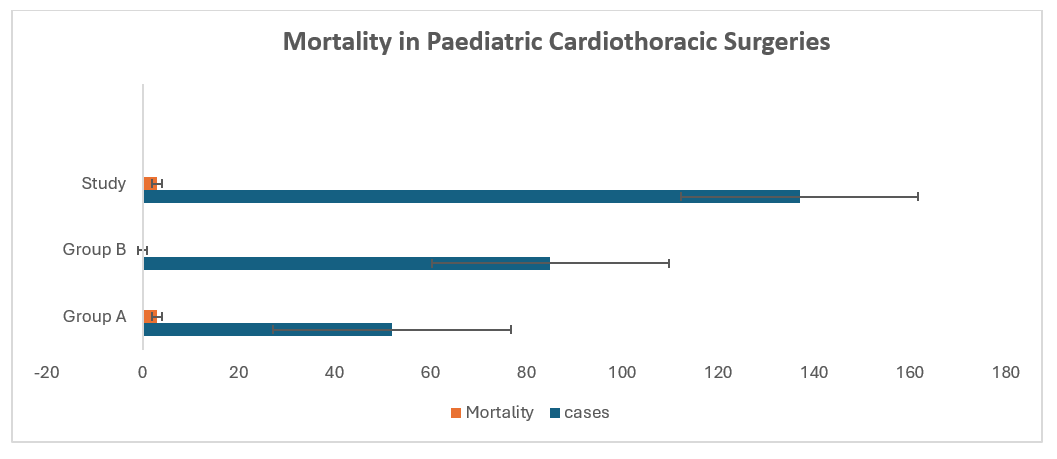

A mortality rate of 2.19% was reported in paediatric cardiac surgeries over the past 15 years. All deaths occurred in Group A, representing a group-specific mortality rate of 5.77%. The first death was due to cerebral malaria, while the other two resulted from ventilator failure, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Postoperative mortality in paediatric cardiothoracic surgery over the past 15 years

As shown in Table 4, the duration, frequency, and percentage of inotrope use in Groups A (n = 51) and B (n = 83). Group A demonstrated significantly longer durations of adrenaline administration (56.72 ± 10.46 hours vs. 17.36 ± 4.64 hours; z = 2.156) and dopamine (13.26 ± 6.57 hours vs. 6.73 ± 2.38 hours; z = 1.977) compared to Group B, based on Mann–Whitney U test results. In contrast, milrinone use did not differ significantly between the groups (z = 1.314).

Chi-square analysis of inotrope usage categories showed a significantly higher proportion of patients in Group B who did not receive any inotropes (22.89% vs. 9.81%; p = 0.026). However, there were no significant differences between groups in the proportion of patients receiving one inotrope (37.25% vs. 39.76%) or two or more inotropes (52.94% vs. 37.35%) (p > 0.05).

| Inotropes | Group A (n=51) | Group B (n=83) | Test-values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adrenaline means ± SD, (%) | 56.72±10.46 h (84.31%) |

17.36±4.64 h (61.45%) |

¥2.156* |

| Milrinone means ± SD, (%) | 32.58±5.31 h (5.88%) |

28.19±3.73 h (3.62%) |

¥1.314 |

| Dopamine means ± SD, (%) | 13.26±6.57 h (27.45%) |

6.73±2.38 h (13.25%) |

¥1.977* |

| No inotrope (%) | 9.81 | 22.89 | £0.026* |

| 1 inotrope (%) | 37.25 | 39.76 | £0.742 |

| 2 or more inotrope (%) | 52.94 | 37.35 | £0.253 |

Table 4: Comparison of inotrope use between Groups

Data presented as means ± SD and percentage. SD: Standard deviation, Z value with Mann–Whitney U test-¥, Chi-square test- £

Table 4 presents the duration, frequency, and percentage of inotrope use in Groups A and B. Adrenaline was the most frequently used inotrope in both groups (84% in Group A and 62% in Group B), while milrinone was the least used (6% and 4%, respectively). The critical Z value at α = 0.05 was 1.645. The observed Z values for adrenaline, milrinone, and dopamine were 2.471, 1.374, and 1.925, respectively, showing a significantly lower use of adrenaline and dopamine in Group B (P < 0.05). For the "no inotrope" variable, the 95% confidence level critical Z value was –1.96, and the observed Z value was 2.151, also indicating a significant difference between the two groups (P < 0.05). However, for the "1 inotrope" and "2 or more inotropes" variables, the observed Z values were 1.248 and 1.572, respectively, showing no significant differences between Groups A and B (P > 0.05).

|

Clinical variables |

Group A (n=51) |

Group B (n=83) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

UFT extubations (%) |

7.84 |

37.31 |

0.015* |

|

Mean duration of mechanical ventilator in postoperative period (h) |

82.34±11.70 |

22.73±6.49 |

0.028* |

|

Mean ICU stay (days) |

3.14±2.37 |

1.91±2.94 |

0.279 |

|

Chest tube drainage (ml) in the first 48 h in the postoperative period |

133±28.46 |

97±15.83 |

0.036* |

|

Mean LOH (days) |

6.87±3.51 |

4.18±3.52 |

0.047* |

|

Re-exploration (%) |

11.77 |

1.21 |

0.018* |

|

Arrhythmia (%) |

5.88 |

1.21 |

0.072 |

|

Central line infection (%) |

3.92 |

1.21 |

0.238 |

|

Hypoglycaemia (%) |

1.96 |

0 |

- |

Table 5: Comparison of clinical variables

*P<0.05 significant, Data presented as means ± SD and percentages. CCU: Cardiac care unit, LOH: Length of hospitalization, SD: Standard deviation, UFT: Ultra-fast track.

Table 5 summarises the comparison of key clinical outcomes between Group A and Group B. The rate of ultra-fast track (UFT) extubation was significantly higher in Group B than in Group A (37.31% vs. 7.84%; p = 0.015). The mean duration of postoperative mechanical ventilation was significantly shorter in Group B (22.73 ± 6.49 hours) compared to Group A (82.34 ± 11.70 hours; p = 0.028). Chest tube drainage in the first 48 postoperative hours was also lower in Group B (97 ± 15.83 mL) than in Group A (133 ± 28.46 mL; p = 0.036). Similarly, the mean length of hospitalisation was significantly reduced in Group B (4.18 ± 3.52 days) compared to Group A (6.87 ± 3.51 days; p = 0.047).

No statistically significant differences were observed in intensive care unit (ICU) stay duration (p = 0.279) or the incidence of arrhythmia (p = 0.072). Re-exploration was significantly more frequent in Group A, as determined by Fisher’s exact test (χ² = 0.0428, p = 0.018). In contrast, the incidence of central line infections did not differ significantly between groups (χ² = 0.577, p = 0.279). Hypoglycaemia was observed only in Group A (1.99%).

DISCUSSION

This 15-year retrospective study of paediatric cardiac surgeries in a West African teaching hospital provides valuable insights into how anaesthetic practices and perioperative management have evolved in Ghana, a low- and middle-income country (LMIC). By comparing two distinct periods, before and after the introduction of the modified WHO operating room safety checklist in 2014. We highlight both the challenges encountered and the progress achieved in improving outcomes for children undergoing complex cardiac surgeries. These findings are interpreted in the context of global standards, existing literature, and the realities of care delivery in resource-limited environments.

A key finding was the steady rise in surgical volumes over time. Between 2007 and 2014, 52 surgeries were performed, compared with 85 between 2014 and 2022, nearly a two-fold increase. This upward trend reflects both the gradual expansion of surgical capacity and improvements in perioperative anaesthesia care. However, progress was interrupted during the COVID-19 pandemic (2019–2021), when restrictions on elective procedures, constrained intensive care resources, and reduced patient mobility led to a decline in surgical numbers. Glasbey et al. reported similar global disruptions in the Surgical Preparedness Index (SPI), assessed across 1,632 hospitals in 119 countries, revealed that expected surgical volume ratios (SVR) were not maintained during the pandemic [11]. Despite these challenges, survival during the latter study period remained excellent.

In Group A (pre-2014), mortality was higher at 5.88%, largely due to non-cardiac causes, including cerebral malaria and ventilator failure. These events prompted a review of anaesthesia practices and the adoption of evidence-based protocols (EBP) in 2014. Subsequently, overall mortality across the entire study period declined to 2.5%, with no mortality after 2014, aligning with international outcomes such as those reported by Berger et al. (3.2% in 1,550 patients) [12]. Careful case selection in the program’s second phase also contributed to improved outcomes.

Initially, simpler congenital anomalies were prioritized, with an Aristotle’s Comprehensive Complexity (ACC) score of 6.9, compared with 7.6 in the later period (Z = -1.41, p < 0.05). Similarly, higher proportions of patients presented with NYHA/Ross Class III post-2014 Vs. pre-2014 (9.41% vs. 5.77%; Z=-0.76, p < 0.05). These findings suggest that, although case complexity increased over time, outcomes continued to improve reflecting the impact of refined perioperative strategies and adaptability to a more challenging case mix. Our results are consistent with the systematic review by Shayan et al., Surgical and postoperative management of congenital heart disease: a systematic review of observational studies [13], which similarly highlighted improvements in outcomes with evolving perioperative management approaches.

The introduction of new protocols in 2014 had significant implications for patient safety, morbidity, and mortality. Key changes included implementation of the modified WHO checklist, prioritization of less complex cases during the transition phase, adoption of early extubation strategies, routine use of tranexamic acid (TXA), relaxation of tight glycaemic control, and rationalization of inotrope use. These interventions align with global trends toward individualized, EBP in paediatric cardiac anaesthesia. International studies, including a systematic review by Qaiser et al. (2024), have shown that checklist use reduces perioperative complications and mortality by improving team coordination, ensuring drug and blood product availability, and enhancing identification of patient-specific risks. Our findings are consistent with reports from other LMIC cardiac centres that successfully adapted the checklist for complex surgeries [14-16].

Extubation in the ICU within six hours, commonly referred to as “fast track,” has been widely studied and shown to reduce morbidity and mortality, lower healthcare costs, and shorten hospital stays [17]. A notable change after 2014 was the introduction of ultra-fast track (UFT) extubation, in which stable patients without contraindications were extubated either immediately in the operating room or within 1–2 hours postoperatively [18]. In earlier years, prolonged ventilation was the standard practice, largely due to limited intensive care staffing and a cautious management approach. Notably, two deaths in Group A (before 2014) were linked to ventilator failure. Following the adoption of UFT extubation protocols, no ventilator-related deaths were reported in Group B (after 2014), reinforcing evidence that early extubation minimizes ventilation-associated complications. These findings are consistent with previous studies [17, 18].

Postoperative haemorrhage remains a major concern in paediatric cardiac surgery, particularly in settings with limited blood bank resources. Previously, haemostasis relied mainly on surgical techniques and transfusion, often leading to blood shortages. After TXA protocols were instituted (20 mg/kg at induction and after protamine), postoperative drainage decreased significantly (133 ± 28.46 ml vs. 97 ± 15.83 ml, p = 0.036), and re-exploration rates fell (11.77% vs. 1.21%, p = 0.018). This mirrors findings from large centre trials supporting TXA as a cost-effective antifibrinolytic [19, 20]. For low-resource settings, TXA provides dual benefits such as haemostatic efficacy and conservation of scarce blood products.

Perioperative glycaemic management also shifted after 2014. Previously, tight glycaemic control was practiced, but this occasionally resulted in hypoglycaemia (1.96% in Group A). Following global evidence, including the NICE-SUGAR trial, which demonstrated increased mortality risk with strict glycaemic control, protocols were adjusted. Administration of small amounts of dextrose-containing solutions in the pre-CPB period effectively prevented hypoglycaemia without pursuing aggressive glucose control [21, 22]. No hypoglycaemic event was reported in Group B.

The rationalization of inotrope use represented another significant advance. While inotropes support myocardial function post-CPB, aggressive use is associated with arrhythmias, ischemia, and increased mortality [23]. Group A required significantly longer durations of adrenaline and dopamine administration compared to Group B, while milrinone use did not differ. Chi-square analysis showed more patients in Group B required no inotropes (22.9% vs. 9.8%, p = 0.026). In Group A, arrhythmias occurred in 5.88% of cases compared with 1.21% in Group B. These findings align with best international practices advocating cautious, evidence guided inotrope use over blanket high dose regimens [24].

Overall, the post-2014 period represented a critical turning point in paediatric cardiac anaesthesia and perioperative care at our centre. Protocol driven yet flexible strategies including structured checklist use, early extubation, TXA administration, rationalised inotrope therapy, and more relaxed glycaemic control were instrumental in improving outcomes, even as case complexity increased and external pressures such as the COVID-19 pandemic emerged. Our experience highlights the value of adapting global best practices to local realities in LMICs, where resource limitations demand innovative, pragmatic, and context specific approaches. Evidence also shows that barriers to care are substantial and manifest differently across various components of the health system and at different points in a patient’s lifetime [25].

The findings of this study are consistent with those reported from another struggling cardiothoracic centre in an LMIC Pakistan [26] and add to the growing literature demonstrating that paediatric cardiac anaesthesia and perioperative care in LMICs can achieve outcomes comparable to those in high income countries when evidence-based protocols are adapted to local realities. It also highlights practical, scalable interventions such as structured checklist use, infection control measures, early extubation, and TXA administration that may serve as models for other centres operating under similar resource constraints.

Study Strengths and Limitations

A major strength of this study is its long duration, spanning 15 years, which allowed the assessment of evolving anaesthetic and perioperative practices over time. It clearly compares two distinct eras before and after the introduction of the modified WHO checklist providing insight into the impact of structured, evidence-based interventions on outcomes in a resource-limited setting. The study also highlights real-world adaptations of global best practices, such as the use of tranexamic acid, early extubation, and rational inotrope management, within the local context of an LMIC. Survival outcomes and perioperative morbidity data were meticulously recorded, offering a comprehensive overview of practice evolution.

However, the study has several limitations. Being retrospective, it is subject to inherent biases in data collection and completeness of records. The sample size is relatively small compared with studies from high-income countries, limiting statistical power for subgroup analysis. Case selection bias may have influenced results, particularly in the early years when less complex procedures were prioritized. The absence of long-term follow-up data restricts conclusions to immediate perioperative outcomes. Finally, findings from a single centre in Ghana may not be generalizable to other LMICs with different healthcare systems and resources.

CONCLUSION

This 15-year review demonstrates that systematic protocol changes implementation of the WHO surgical safety checklist, early extubation, routine tranexamic acid use, rational inotrope management, and relaxed glycaemic control significantly improved outcomes in paediatric cardiac surgery in Ghana despite increasing case complexity and resource constraints. These findings underscore the value of adapting global best practices to local realities in low and middle income countries, where pragmatic, patient-tailored strategies can achieve safe and effective care.

Ethical policy and institutional review board statement:

Ethical clearance and approval were obtained from Research and Development Unit at KATH No. RD/CR16/295 as per the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 and revised guidelines of 2024.

Financial support and sponsorship: Nil.

Conflicts of interest: There are no conflicts of interest.

Contributor ship statement:

SS: Performed anaesthesia in most cases, obtained ethics approval, data collection, analysis, protocol implementation, wrote the manuscript, and critical review of the manuscript.

DEM: Data analysis, critical review of the manuscript.

NAB: Performed anaesthesia in most cases, obtained ethics approval, data collection, analysis, protocol implementation and critical review of the manuscript.

References

1. Li Y, He C, Yu H, Wu D, Liu L. Global, regional, and national epidemiology of congenital birth defects in children from 1990 to 2021: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2025; 25 (1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-025-07612-1

2. Manuel V, Miana LA, Edwin F. Narrative review in pediatric and congenital heart surgery in sub-Saharan Africa: challenges and opportunities in a new era. AME Surgical Journal. 2021; 1 Available from: https://doi.org/10.21037/asj-21-34

3. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/birth-defects .

4. Murala JSK, Karl TR, Pezzella AT. Pediatric Cardiac Surgery in Low-and Middle-Income Countries: Present Status and Need for a Paradigm Shift. Frontiers in Pediatrics. 2019; 7 Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2019.00214

5. Owusu-Sekyere F, Goka B, Adzosii D, Obeng W, Yawson A, Akyaa-Yao N,<i>et al</i>. Cardiovascular physical examination as a screening tool for congenital heart disease in newborns at a teaching hospital in Ghana. Ghana Medical Journal. 2023; 57 (2). Available from: https://doi.org/10.4314/gmj.v57i2.10

6. Danso KA, Appah G, Akuaku RS, Karikari YS, Ansong AK, Adwin F,<i>et al</i>. Prevalence of Congenital Heart Disease in Children and Adolescents Under 18 in Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World Journal for Pediatric and Congenital Heart Surgery. 2025; 16 (3). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/21501351241299405

7. Singh S, Okyere I, Singh A. Paediatric Cardiac Anaesthesia Perspective in Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital Kumasi. Nigerian Journal of Medicine. 2022; 31 (2). Available from: https://doi.org/10.4103/njm.njm_12_22

8. Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospita. https://www.moh.gov.gh/komfo-anokye-teaching-hospital

9. Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital. 2023 Report. https://kath.gov.gh/our-history/ 2023 report

10. Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection. 507 Republic of Ghana. https://www.mogcsp.gov.gh

11. Glasbey JC <i>et al</i>. Elective surgery system strengthening: development, measurement, and validation of the surgical preparedness index across 1632 hospitals in 119 countries. The Lancet. 2022; 400 (10363). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01846-3

12. Berger JT, Holubkov R, Reeder R, Wessel DL, Meert K, Berg RA<i>et al</i>. Morbidity and mortality prediction in pediatric heart surgery: Physiological profiles and surgical complexity. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2017; 154 (2). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.01.050

13. Shayan RG, Dizaji MF, Sajjadian F. Surgical and postoperative management of congenital heart disease: a systematic review of observational studies. Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery. 2025; 410 (1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-025-03673-0

14. Chirag R. Parikh, William R. Zhang. Role of Novel Kidney Injury Biomarkers in Perioperative Acute Kidney Injury. Perioperative Kidney Injury. 2015; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-1273-5_3

15. Nikhil Mudgalkar. Blood transfusion in cardiac surgery- need to follow basics!. Perspectives in Medical Research. 2020; 7 (3). Available from: https://doi.org/10.47799/pimr.0703.01

16. Qaiser S, Noman M, Khan MS, Ahmed UW, Arif A. The Role of WHO Surgical Checklists in Reducing Postoperative Adverse Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2024; Available from: https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.70923

17. Ng-Kamstra JS, Nepogodiev D, Lawani I, Bhangu A, Workneh RS. Erratum to ‘Perioperative mortality as a meaningful indicator: Challenges and solutions for measurement, interpretation, and health system improvement’ [Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain Med. 39 (5) (2020) 673–681]. Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain Medicine. 2020; 39 (6). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accpm.2020.10.005

18. Luo RY, Fan YY, Wang MT, Yuan CY, Sun YY, Huang TC, <i>et al</i>. Different extubation protocols for adult cardiac surgery: a systematic review and pairwise and network meta-analysis. BMC Anesthesiology. 2025; 25 (1). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-025-02952-z

20. Singh LC, Singh S, Okyere I, Annamalai A, Singh A. Comparison of effectiveness and safety of epsilon-aminocaproic acid and tranexamic acid in adult patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Journal of Medical Society. 2022; 36 (2). Available from: https://doi.org/10.4103/jms.jms_149_21

21. Sanjeev Singh, Rachna Mishra, Arti Singh. Comparative Study Between a Combination of Tranexamic Acid, Oxytocin and Carboprost Tromethamine Versus Ethamsylate and Oxytocin in Preventing Primary Postpartum Haemorrhage in High-Risk Women Undergoing Caesarean Delivery. Journal of Obstetric Anaesthesia and Critical Care. 2025; 15 (2). Available from: https://doi.org/10.4103/joacc.joacc_49_24

22. James S. Krinsley, Jean-Charles Preiser. Is it time to abandon glucose control in critically ill adult patients?. Current Opinion in Critical Care. 2019; 25 (4). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1097/mcc.0000000000000621

23. Loeffelholz CV and Birkenfeld AL. Tight versus liberal blood-glucose control in the intensive care unit: special considerations for patients with diabetes. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology. 2024; 12 (4). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-8587(24)00058-5

24. Singh S, Singh A, Rahman MM, Mahrous DE, Singh LC. Is the combination of conventional ultrafiltration and modified ultrafiltration superior to modified ultrafiltration in pediatric open-heart surgery?. Journal of Medical Society. 2023; 37 (3). Available from: https://doi.org/10.4103/jms.jms_104_23

25. Jentzer JC, Coons JC, Link CB, Schmidhofer M. Pharmacotherapy Update on the Use of Vasopressors and Inotropes in the Intensive Care Unit. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2015; 20 (3). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/1074248414559838

26. Vervoort D, Jin H, Edwin F, Kumar RK, Malik, Tapaua N, <i>et al</i>. Global Access to Comprehensive Care for Paediatric and Congenital Heart Disease. CJC Pediatric and Congenital Heart Disease. 2023; 2 (6). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjcpc.2023.10.001

27. Khan A, Abdullah A, Ahmad H, Rizvi A, Batool S, Jenkins KJ, <i>et al</i>.. Impact of International Quality Improvement Collaborative on Congenital Heart Surgery in Pakistan. Heart. 2017; 103 (21). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2016-310533

Copyright

©2025 (Singh & Boateng). This is an open-access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License CC-BY 4.0. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original authors and source are credited.

Cite this article

Singh S, Boateng NA. Paediatric Cardiac Surgeries: A 15-Year Retrospective Study at Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital, Ghana. Perspectives in Medical Research 2025; 13(3):170-177 DOI:10.47799/pimr.1303.25.72